“No experience is in itself a cause of our success or failure. We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences—the so-called trauma—but instead we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.”

One of the greatest actors of our time is Daniel Day-Lewis. He stars in three of my favorite films: Lincoln, Gangs of New York, and There Will Be Blood. Of the three, There Will Be Blood stands apart, not just for its cinematic mastery and storytelling, but for what it reveals about the human condition when paranoia, neurosis, and pain rule over a man.

On the surface, it’s a story about capitalism and religion. But underneath, it’s a study of a man consumed by his own belief that the world is out to rob him of happiness. Daniel Plainview, played by Day-Lewis, isn’t undone by competitors, nor by faith or economics, nor even by his harsh circumstances. He’s undone by himself.

“I have a competition in me. I want no one else to succeed. I hate most people.”

— Daniel Plainview

Plainview sees himself as a victim. He distrusts everyone, strikes first, and assumes betrayal at every turn. He uses aggression as preemption. He believes he’s defending himself. But in truth, he destroys everyone around him. And in the end, he stands alone, not because he lost, but because he never had the courage to live differently.

His obsessive drive, his possessiveness, and his fear metastasize into a quiet, brooding psychosis based on a lie about the way the world and life work. His success becomes his prison. His wealth is his punishment. His internalized trauma and anger are his condemnation. The literary irony is that Daniel Plainview doesn’t lose. He gets exactly what he sent out to get, and it leaves him empty.

There Will Be Blood takes place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and during that time, another man was alive who could have shown Plainview a different path and saved himself from his self-destructive entropy.

Plainview is a fictional character, but his arc is anything but fiction. His descent into isolation and bitterness is just an exaggerated version of something we all witness today. Only now does it play out in comment sections, therapy speak, and the slow erosion of the social fabric. Plainview’s emotional spiral, rooted in a self-authored victim narrative of “me against the world,” mirrors the same dynamics we see now, simply dressed in new language and filtered through modern media.

The pathology of victimhood isn’t new. It’s been rebranded and recast for today. Social media, modern therapy, and Gen Z identity politics may amplify it, but the pattern itself is ancient. This isn’t a generational glitch. It’s human nature.

There’s a long history of research on the psychology of victimhood and the weaponization of weakness. History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. Over the past few years, I’ve gone deep into this subject through my “Nice Guy” series. Along the way, I’ve read almost everything on the topic: Bad Therapy, The Rise of Victimhood Culture, The Coddling of the American Mind, Wronged, Nation of Victims, Emotional Blackmail, Leadership and Emotional Sabotage, and more.

The theme is consistent: modern culture rewards superiority and control, often cloaked in a facade of helplessness. It excuses nearly any behavior or belief, as long as it’s delivered through the voice of the wounded. In today’s economy of attention and outrage, self-declared victimhood is currency, and it spends well.

The Internet has turned content into a commodity, and we’re drowning in it. Disorientation naturally follows. We often forget the past or distort it due to recency bias. We mistake what we’ve been told in school or what we scroll past online for original thought. But most of what we call “new thinking” is just recycled ideology and rebranded propaganda.

To understand how we arrived at this moment and how cultural narratives are shaped by thinkers most people have never heard of, start with Foucault. He’s the intellectual architect of the modern left’s obsession with power over truth. Meanwhile, the rise of Moral Therapeutic Deism, the soft-spoken spirituality of contemporary America, was outlined decades ago by Philip Rieff.

Today, many blame the rise of the victimhood complex on Marxism, the far left, or the collapse of Christianity and Western values. And while there’s truth in that, I’d argue it misses the deeper reality. The desire to be the wounded one, to be seen as the wronged party in every situation, isn’t ideological. It’s elementary. It predates America, Marx, and postmodernism.

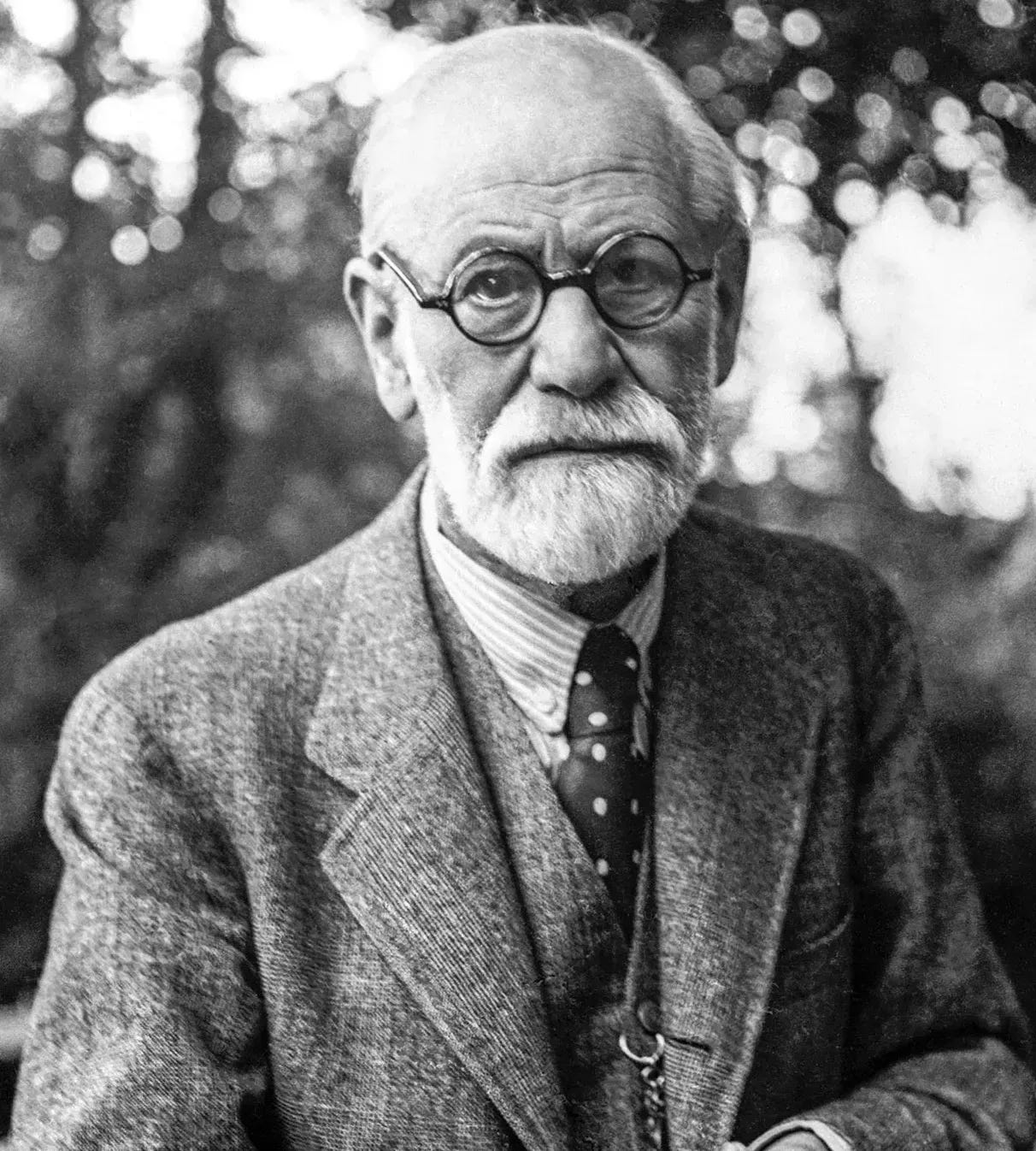

The psychological rot we’re swimming in today was identified long before most of us were born. A psychotherapist lived during the same period as Daniel Plainview. He studied the same neuroses and self-destructive patterns that led Plainview to his downfall, and he offered a way out.

He understood that both inferiority and superiority complexes are rooted in the fictional narratives we tell ourselves about how life and the world should work, as well as in interpersonal issues. When we let those lies define us, we surrender our agency and freedom of choice. We lose control and we lose our identity. Adler offered a path out of that prison, a way back to freedom through work, relationship, contribution, and meaning.

That man was Alfred Adler.

A Nice Guy’s Trauma

"Like any intervention with the potential to help, therapy can harm."

— Bad Therapy

When I concluded A Christian Look at No More Mr. Nice Guy, I wanted to outline the historical context of the “Nice Guy” pathology. While shaped by modernity, it didn’t start with Dr. Glover. It exists within a broader stream of human history, a lineage that builds upon itself. The foundational building blocks of the Nice Guy are much older. Our modern, digitally-driven environment may amplify the Nice Guy effect, but nothing catches fire unless it taps into something primal. Every so-called modern affliction is, in reality, just an ancient instinct re-skinned for today. The Nice Guy syndrome is no different.

At the core of the Nice Guy spiral are a set of learned behaviors: approval-seeking, covert contracts, guilt-based manipulation, emotional dishonesty, and fear disguised as kindness. These aren’t strategies for living — they’re coping mechanisms for control and superiority. They’re just wrapped in different paper than Plainview, but the purpose and pathology are still plain to see. The Nice Guy is striving toward a goal, often without being fully aware of it. He’s chasing avoidance: avoiding rejection, shame, and discomfort, while also seeking superiority and hidden competition with others. Plainview’s approach is more culturally obvious, and Nice Guy’s approach is more subtle and manipulative. Both sides of the same coin.

As I wrote:

“Nice guys will sacrifice their needs to return back to a fake armistice… masked in passive-aggressive niceties. They consider themselves victims of circumstances and others, so they return to delivering more appeasement and approval-seeking.”

The uncomfortable truth is this: Nice Guys think they’re victims, but they’re not. They’re the ones holding the keys to their own prison and lack the courage to leave it, just like Plainview.

Nice Guys aren’t failing. They’re succeeding at achieving exactly what their behavior is designed to produce, whether they realize it or not. The cycle of shame, appeasement, and quiet resentment is the direct result of their choices. They could walk away. They don’t. That’s why being a Nice Guy is fundamentally a neurosis.

This is precisely what Dr. Robert Glover outlined in the original text:

“Nice Guy Syndrome is a shame-based disorder, and it’s also an anxiety-based disorder. Pretty much everything Nice Guys do, or don’t do, is an attempt to manage their anxiety… Just about everything a Nice Guy does is consciously or unconsciously calculated to gain someone's approval or to avoid disapproval.”

Curing men of the Nice Guy syndrome requires two things: awareness of how they perpetuate their own pathology and the courage to choose differently with better, healthier goals.

This sounds remarkably similar to another well-known book: The Courage to Be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga.

If you haven’t read it, the book is structured as a dialogue between a frustrated, self-sabotaging young man — obsessed with how others perceive him — and a wise philosopher, who happens to be a student of Alfred Adler. The young man is angry, bitter, and exhausted. He blames the world for his pain and is constantly frustrated by other people’s behavior. He’s trapped in a loop of people-pleasing, blame, and the refusal to change, which he rationalizes as “an inability.” In other words: he’s a textbook Nice Guy but with a variant cursory symptoms.

“The courage to be happy also includes the courage to be disliked. When you have gained that courage, your interpersonal relationships will all at once change into things of lightness.”

— Ichiro Kishimi, The Courage to Be Disliked

In the book, the philosopher cuts through the noise. His diagnosis? Victimhood is a lie we tell ourselves to avoid responsibility. The world isn’t holding you back. You are doing this to yourself.

Before “woke” ideology, before Twitter discourse, before victimhood became social currency, Adler saw the same pattern: people drawn to neurotic helplessness, clinging to their past as an excuse to avoid their future. These individuals disregarded truth in favor of trauma, choosing stasis over change. They lived in a deep, paralyzing belief that the world was against them — a belief built on covert contracts, and the assumption that history is destiny. These lies justified their inaction, their bitterness, and their autobiographical victimhood.

“Your unhappiness cannot be blamed on your past or your environment. And it isn’t that you lack competence. You just lack courage. One might say you are lacking in the courage to be happy.”

— Ichiro Kishimi, The Courage to Be Disliked

The Father of Victimhood

The idea that we are bound by what happened to us is not new. Just as Nice Guy Syndrome has an author, so does etiological victimhood—deterministic trauma. He didn’t invent it or discover it, but he defined it and gave it categories. His name was Freud.